Miss Cunningham donned atop her signature white horse, left her hometown of Fitzgerald, GA, to join the Silas Green Show as a circus rider. The Silas Green Show was a major circus, traveling across the country with a 16-piece band and the main tent that could hold a whopping 1,400 spectators. Blues legend Muddy Waters briefly joined the Show, as did Bessie Smith. The group was so popular that Jet Magazine once called it “almost as much a part of southern culture as collard greens and barbecue ribs.” Cunningham eventually left the Show, still on horseback, and headed for the city. Her next venture would prove even more pivotal.

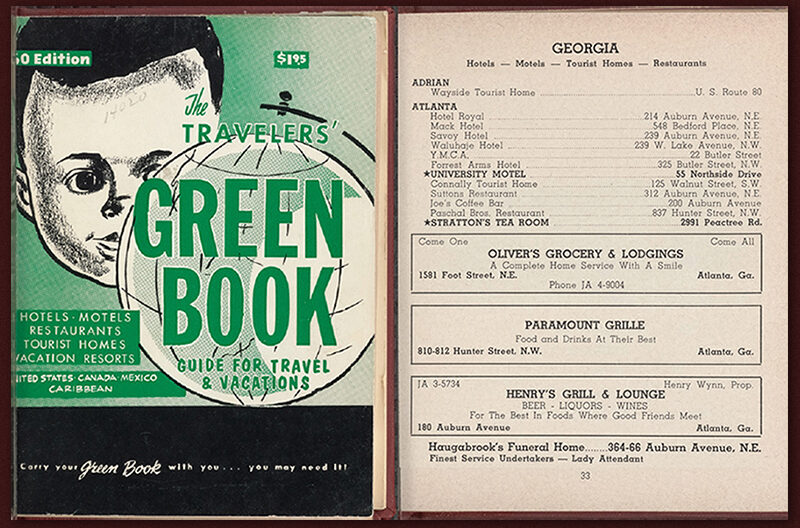

A look back at how the Negro Motorist Green Book shaped Auburn Avenue.

During the time of the Jim Crow South, segregated Atlanta was a particularly challenging environment for African Americans. This image from signage at Ponce De Leon Springs Park reminds us that African Americans were not usually welcome to enjoy the pleasures of public life in Atlanta.

Jim Crow

In fact, throughout the Jim Crow South, a time when racism, prejudice, and legally prescribed discrimination were the order of the day, it was neither unlikely nor abnormal for Black travelers to run into challenges gaining service with white-owned businesses while on the road. The challenges could include things as benign as vehicle repair, and being refused lodging and food at hotels. Or even worse, many could face threats of physical violence and forcible expulsion from whites-only “sundown towns.”

The Jim Crow Era, a time where racism, prejudice, and legally prescribed discrimination was as American as apple pie. It was not unlikely or abnormal for Black travelers to run into challenges gaining service with white-owned businesses while on the road.

The challenges could include things as benign as vehicle repair and being refused lodging and food at hotels while on the road. Or even worse, many could face threats of physical violence and forcible expulsion from whites-only “sundown towns.”

Victor Hugo Green

The Negro Motorist Green Book in 1936

The seemingly unavoidable dangers and inconveniences faced by Black travelers prompted a postal carrier from Harlem, NY by the name of Victor Hugo Green to publish The Negro Motorist Green Book in 1936. The Green Book, as it became to be known, was a publication containing businesses that were warm and welcoming to Black travelers. Green compiled resources “to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable” [1] Organized by state, The Green Book contained the names and addresses of hotels, motels, tourist homes, restaurants and other services that were safe for Blacks to patronize.

For sale by subscription and available for purchase at Esso gas stations, at its height, the Green Book sold 2 million copies per year. In the 1948 edition, Green prophetically wrote these words, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. This is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.” Green unfortunately never got to see the change he wrote about because he died before the passing of the Civil Rights Act (essentially eradicating the need for the guide). 1967 was the last year The Green Book was published, however, it is extremely important for us to look at it not just as a historic travel guide.

Rather, The Green Book represents one of myriad tools used to thrive in much less than ideal circumstances.

Auburn Avenue

By the time the Green Book was first published in 1936, the Sweet Auburn community was arguably the center of African American commerce, politics, spirituality in Atlanta. Nestled along a short, but sweet, mile and a half of Auburn Avenue, the Sweet Auburn Historic District is a beautiful reflection of the history, heritage, and achievements of African American’s in the city of Atlanta. It is no wonder that of the sixteen locations listed in the 1950 edition, seven called their home the Sweet Auburn community.

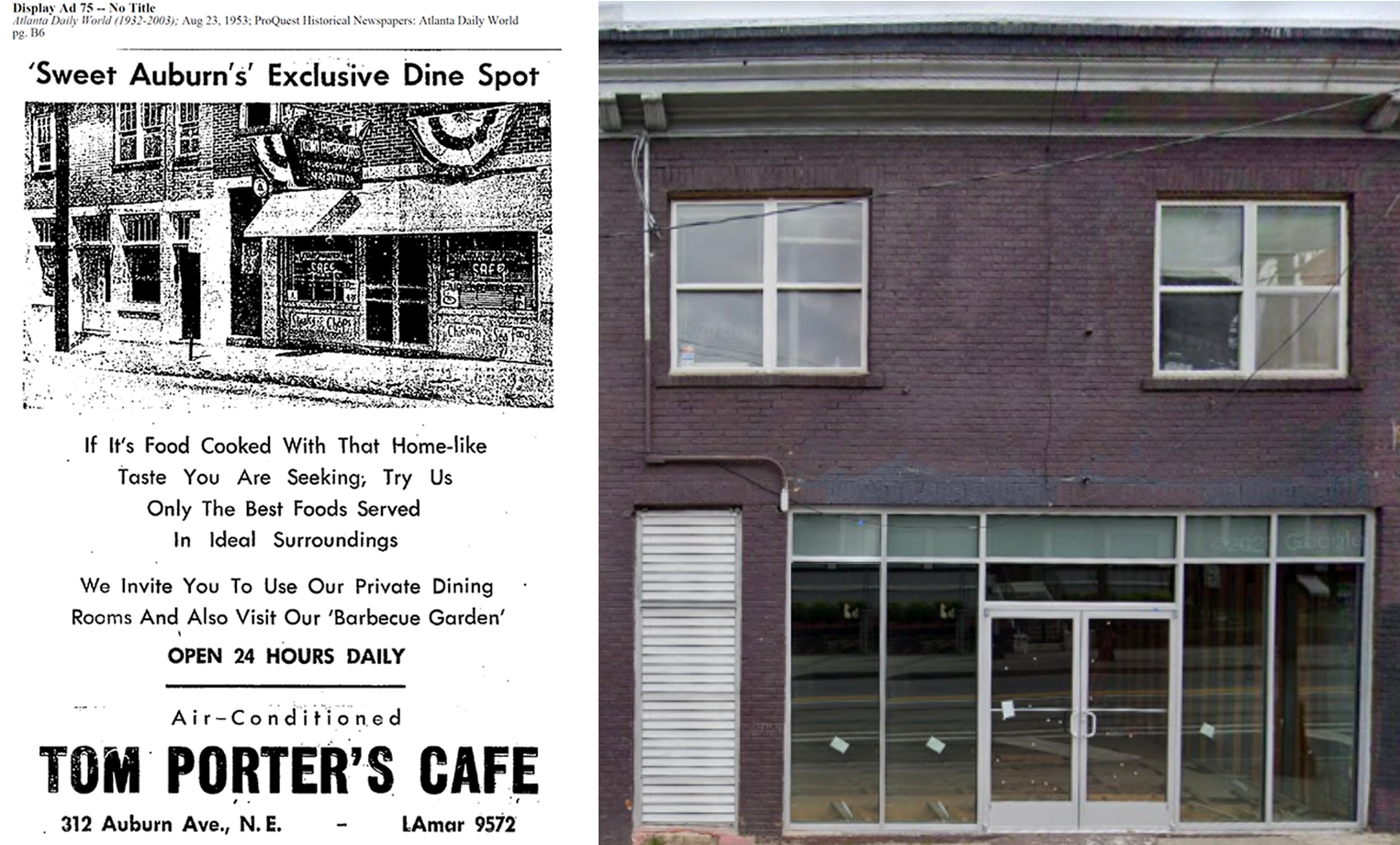

Sutton’s Restaurant

Many of Sweet Auburn’s most notable businesses were started and run by exceptional African American women entrepreneurs. The Green Book of 1950 documents this fact by listing three women-owned enterprises of the seven total.

Scottie B. Sutton, affectionately known as “Ma Sutton” was born around 1882 and came to Atlanta in the early twentieth century from Washington, Georgia. Getting a start in her career by serving a white family on Peachtree Street, Ma Sutton went on to open up her own restaurant in 1918, located at 312 Auburn Avenue. Sutton’s Restaurant served “southern specialties” and was popular among the likes of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and other Black celebrities who were refused service at whites-only restaurants when they toured Atlanta. Ma Sutton retired in 1950 and the restaurant closed in 1953.

Below is an excerpt from the book, “Living Atlanta: An Oral History of the City, 1914-1948” by Clifford M. Kuhn on Ma Sutton told by one Horace Sinclair:

“They called her Ma Sutton,” recalls Sinclair. “Everybody all over the country would come to Atlanta and go get a decent meal at Ma Sutton’s. She would really set the table. You’d get everything on the table just like you would be at home, serve yourself. You’d have meats and vegetables of all kinds, light rolls, cornbread, coffee, milk, or tea. She’d even put preserves on the table, all that stuff.”

The Hotel Royal

Carrie Cunningham started in hospitality renting rooms on Decatur Street, and in 1937 she put it toward the purchase of the hotel on the upper floors of the Citizens Trust Bank on Auburn. Renamed the Hotel Royal (1), it flourished in the center of Black life in Atlanta and was a refuge for those African-Americans traveling in the Jim Crow south.

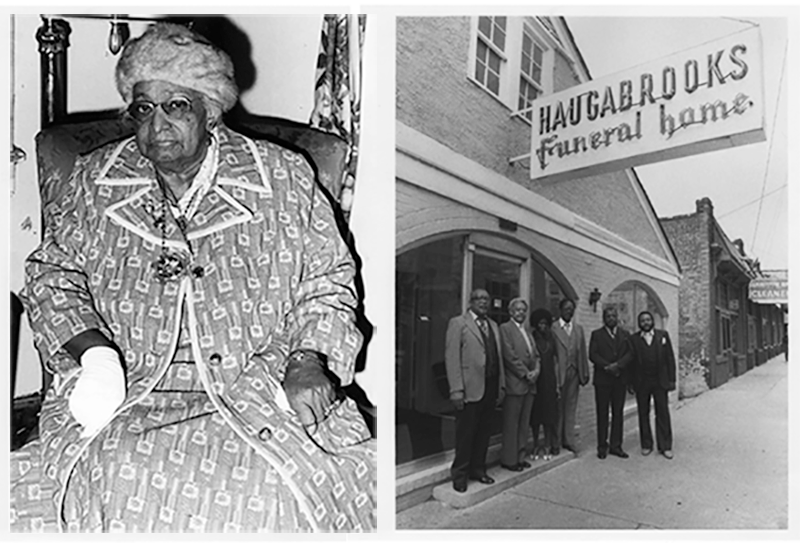

Haugabrooks Funeral Home

Before establishing Haugabrooks Funeral Home in 1929, Mrs. Geneva Morton Haugabrooks worked as a cook for Governor Station for roughly eight years and also worked as a schoolteacher. A pillar in her community, Mrs. Haugabrooks was noted for her many accomplishments and outstanding service in the community by the NAACP, the Urban League, the Young Men’s Christian Association, Atlanta’s African American churches, National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, Inc., National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, Inc., (then) Georgia Governor, Mr. Joe Frank Harris, and many more.

Mrs. Haugabrooks was greatly respected and highly revered as one of the earlier African American pioneers of Atlanta’s Black businesses. She was also known as one of the few Black women entrepreneurs on Auburn Avenue.

Haugabrooks Funeral Home is operating today as a Special Events Venue by HDDC, also located on Auburn Avenue.

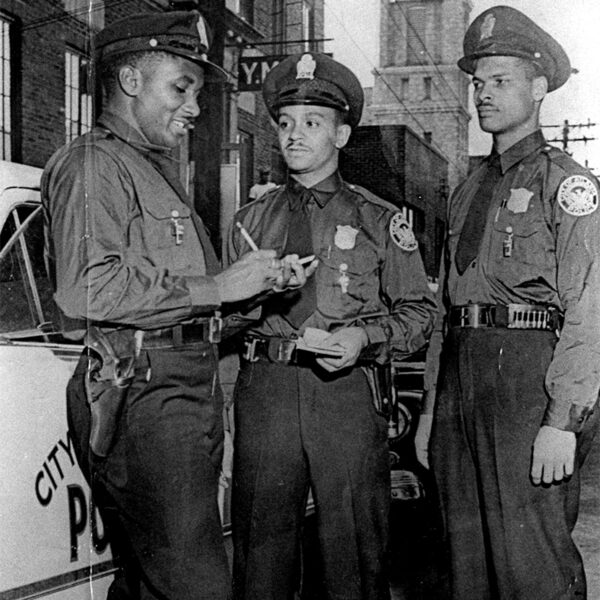

Butler Street YMCA

Known as the “Black City Hall” for much of its existence, the Butler Street YMCA or simply, “The Y”, became a center of social life for Blacks in Atlanta by providing recreation as well as a safe and supervised activity space for the city’s Black youth. Even Martin Luther King, Jr. was a member at the Y as a young man and was undoubtedly influenced by the sense of family, activism, and brotherhood held within the walls of the building. The Butler Street YMCA not only served as a center for youth development but also as a meeting place for the city’s Black leaders, with groups like the Atlanta Negroes Voters League and All Citizens Registration Committee regularly meeting at the Y.

The building contains over 10,000 square feet and houses 48 dormitory rooms, 7 classrooms, a small auditorium, a gymnasium, an indoor track, a swimming pool, showerbaths, a café, and restrooms. It is the only minority YMCA in America that has been allowed to operate independently.

In 1948, Atlanta hired the first Black police officers and was stationed in the basement of the Butler Street YMCA.

The Savoy Hotel

Keeping in the theme of providing sanctuary for Black travellers during Jim Crow, oftentimes hotels that welcomed Blacks would be housed in the homes of Atlanta residents and also inside of multipurpose buildings.

Constructed in 1924 by Alonzo Herndon, the founder of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, as an office structure to compete with the Odd Fellows office complex across the street built by black millionaire Benjamin J. Davis, the Herndon Building was a multi-purpose economic development site that covered a city block and housed the following: medical and dental offices, the Atlanta School of Social Work, the thirty-four room Savoy Hotel, B.B. Beamon’s Restaurant, the Atlanta Urban League, a furniture store and other retail shops, a gas station next door, and over the years much more.

The Herndon Building was unfortunately destroyed by a tornado that hit downtown Atlanta in 2008.

Now and Then

The Royal Peacock

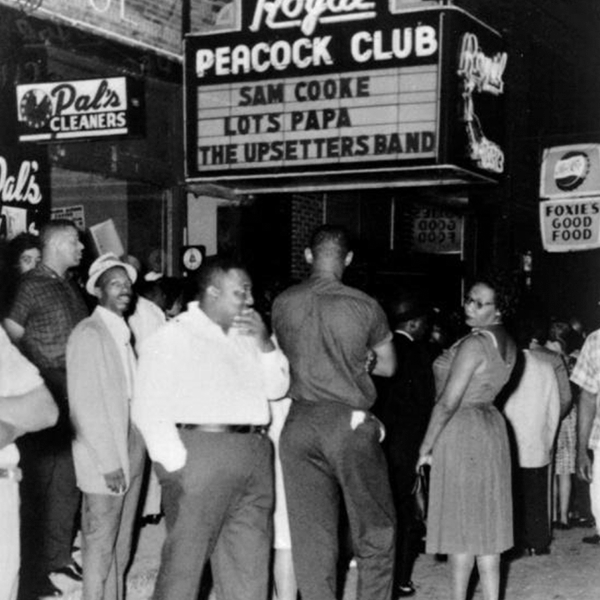

Though not officially listed in The Green Book, The Royal Peacock was a premier destination for Black travelers looking to see the most popular African American entertainment figures in the country.

Though not officially listed in The Green Book, The Royal Peacock was a premier destination for Black travelers looking to see the most popular African American entertainment figures in the country. Having housed famous acts such as Aretha Franklin, Little Richard, Marvin Gaye, and James Brown, to name a few, the Royal Peacock, known affectionately as “Club Beautiful,” was once revered as the swankiest club in Sweet Auburn.

Opening its doors in 1937 as The Top Hat Club, Carrie Cunningham bought it in 1949 and renamed The Royal Peacock, a festive name to match the colorful feathers that adorned the wall. The Royal Peacock could hold roughly 350 patrons but would often house hundreds more than was permitted, with some people opting to stand on tables and chairs all for a glimpse of the undeniable talent on stage. The lines for shows would snake around the block.

As you can see, the same block was a true safe-haven for African American travelers, as from left to right, you will notice Henry’s Grill, The Royal Peacock, Joe’s Coffee Bar, and Hotel Royal (on the far right next to the Big Bethel Sanctuary) all within easy walking distance of each other.

Today, those same buildings host the next generation of entrepreneurs serving the Sweet Auburn community much as they did over seventy years ago.